In the Light of the Constant Moon

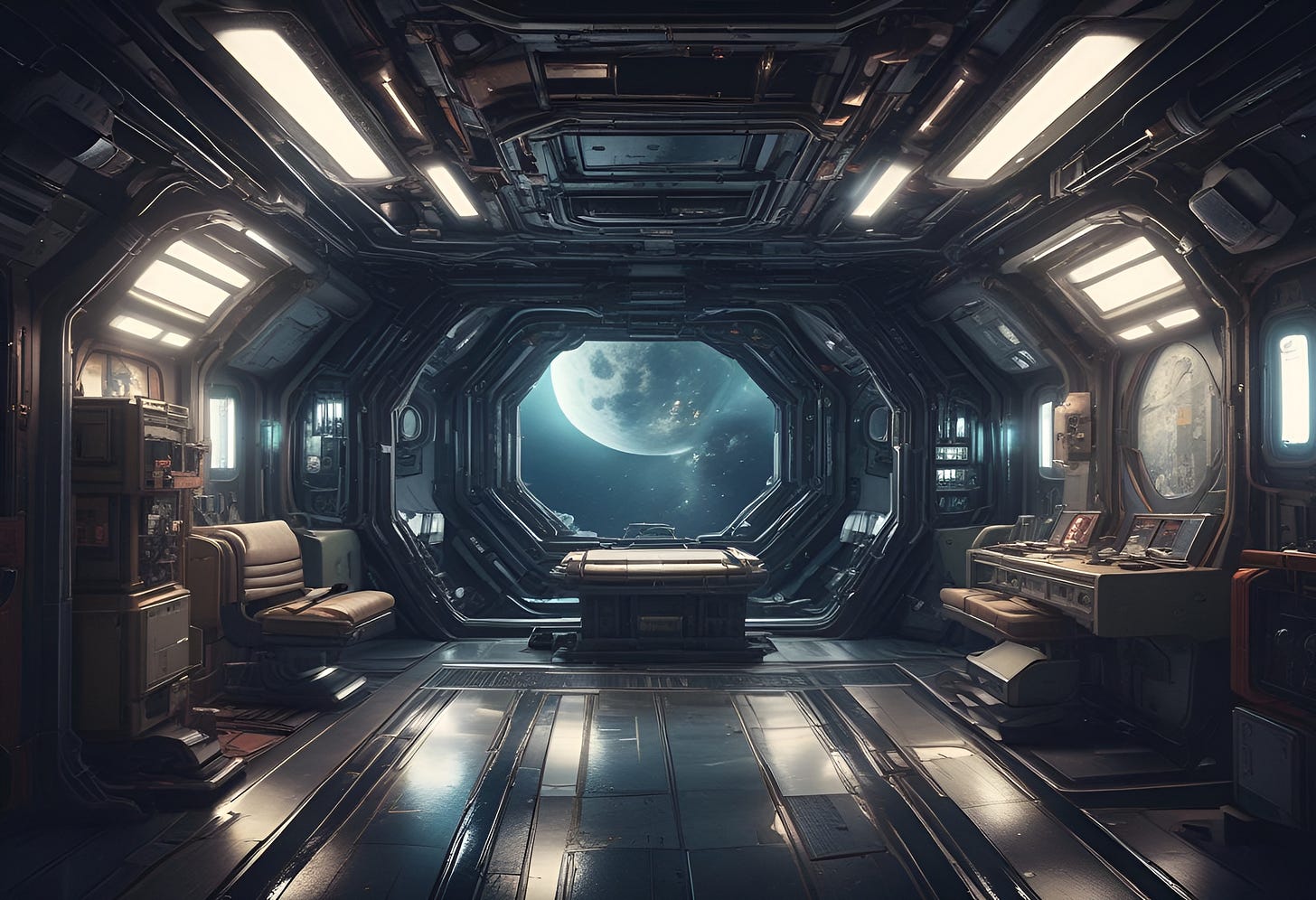

Short Fiction: A space station prepares for the arrival of a new crew, but someone is not who they seem to be

“When they found her body,” Fleming said, “she’d been torn to pieces. Nearly unrecognizable.”

Rowland listened as the doctor spoke. He’s a master storyteller, she thought.

She strained to hear his words over the hiss of the oxygen generators and the constant flexing of the old station’s inner hull.

“Of course,” Fleming continued, “they didn’t have a real grasp of psychology in the sixteenth century. To the authorities, only a monster could’ve done such a thing—some kind of horrific beast.”

“That fascinates me,” Rowland said. “The old twentieth-century monster movies I loved as a kid were based on some sixteenth-century version of Jeffrey Dahmer who murdered and cannibalized a villager,” Rowland said.

Fleming nodded slowly.

“And the stories outlived the facts. They turned killers into legends. Vampires. Werewolves. All that.”

Fleming’s mouth twitched. “But things were so much better in the old days, weren’t they?” His tone dripped with sarcasm.

Rowland laughed. “Yeah. Right.”

The irony of discussing medieval folklore while approaching geostationary orbit around the moon, eighty-eight thousand kilometers above the surface, wasn’t lost on her—but you had to do something to break the monotony.

Lieutenant Audrey Rowland studied the doctor. Attractive, she thought, but too old for me. She’d been alone on the station almost one hundred eighty days when he arrived. A romantic fling might’ve been nice, but she was simply grateful for conversation. They’d spent the past two days telling stories while they waited for the shuttle. It had been Fleming’s idea to shut off the lights and talk by the glow of the emergency lamps.

“The cabin LEDs are too harsh,” he’d said.

So they swapped horror stories under amber light, like campfire tales she’d loved as a kid back on Earth.

A crumb from Fleming’s protein bar floated away. He caught it midair and popped it into his mouth. Rowland, used to the station’s one-G wheel, had been floating more often lately, joining him in the weightless “cathedral” where the moon hung bright and enormous beyond the window.

“Eventually,” Fleming said, “they zeroed in on Peter Stumpp.”

“He was the killer?”

“That’s what they said. Supposedly killed eighteen people—women, children—over twenty-five years. Mutilated and cannibalized them,” Fleming replied.

“My god.”

“I know. Terrible—but just the sort of thing we see in the news every day now.”

“And they thought he was… a monster?” she asked.

“Of course. They claimed he’d made a pact with the Devil. Lucifer gave him a magic belt that let him turn into a wolf—stronger, faster, more savage.”

A soft tone sounded from the control panel. Rowland drifted over to check the readouts. The deep metallic groan of the hull echoed like a sigh.

“How’d you end up on this assignment?” Fleming asked.

“Held over after the last crew. Nobody volunteered, so they volunteered me.” She smirked. “What about you?”

Doctor Fleming looked away as he spoke, in a manner that made her wonder whether he was ashamed to be there.

“Well,” he said. “I requested this assignment.”

“Seriously? You were head of UEA Medical Operations. Why trade that for this rust bucket?”

“Ah, the old ‘difference-of-opinion’ dilemma,” Fleming answered.

“Meaning?”

“The Alliance doesn’t always appreciate my research priorities.” He smiled faintly. “Out here, there’s time to focus on what really matters.”

He turned toward the viewport. He could see a slowly disappearing sliver of darkness on the moon’s horizon as the lunar station approached geostationary orbit.

“So,” Rowland asked, “how does your story end?”

“They tortured Stumpp until he confessed—claimed he’d practiced witchcraft since he was twelve. Incest, cannibalism, you name it.”

“Under torture?” she said. “People will say anything.”

Fleming’s dark eyes caught the light. He was broad-shouldered, rugged for a man of medicine.

“They put him on a wheel,” he said quietly, “tore his flesh with red-hot pincers. Broke his limbs with the blunt side of an axe so he couldn’t rise from the grave.”

“Jesus Christ.”

“Then they beheaded him and burned the body. His mistress and thirteen-year-old daughter were executed too,” Fleming concluded.

A loud tone blared. Rowland flinched.

“Geostationary orbit in ten minutes,” the computer announced.

“How far out’s the shuttle?” Doctor Fleming asked, the campfire spell broken.

“Forty-five minutes.”

“Cut it kinda close, didn’t you?”

“Couldn’t push this heap any faster without ripping her apart,” she said. “We’ll be locked-in before they dock.”

Audrey tapped another of the old station’s control panels.

“Thanks for the warm welcome, by the way,” Fleming said. “Hot coffee and real food—wasn’t expecting that.”

“My pleasure,” she said.

“Maybe you’ll greet the new crew the same way?” he asked.

Rowland smiled. “I’ll get started in the galley.”

She drifted down the central hub to the wheel, climbed the ladder, and felt gravity return beneath her boots. The galley lights flicked on—and the hatch above her slammed shut.

A hiss. Then an alarm.

DECOMPRESSION SEQUENCE INITIATED.

Doctor Fleming’s face appeared on the screen as the hull groaned once more.

“Do you ever wonder if science got it all wrong, Rowland?” the doctor asked.

“Fleming, what the hell are you doing?”

“Geostationary orbit in six minutes,” the computer called out.

“We’ve spent all this time assuming tales of monsters and werewolves were misidentified serial killers and lunatics,” Fleming said.

Lieutenant Rowland’s ears popped as the air pressure dropped in the galley.

“But what if we’ve got it backwards?” Fleming asked. He had a crazy look in his eye.

“What if we’ve been misidentifying monsters as run-of-the-mill serial killers?” he asked.

“Fleming, open the hatch!” she shouted, pounding the keyboard. “I can’t breathe!”

“I’ve already revoked your credentials,” he said, emotionless.

“Fleming, please! I’m going to die in here!”

Fleming stared intently into his camera.

“It’s such a cruel tragedy,” he said. “To have this genetic gift in your family, but you’re only able to enjoy it once a month. There’s no sensation like it.”

“Geostationary orbit in four minutes.”

“Your heart pumps faster and your body feels like it’s operating at 200% capacity when the moon is full. The feeling you get when you spring from the shadows and rip the throat out of an unsuspecting victim is incomparable ecstasy,” the doctor offered.

“You’re insane!” she gasped, struggling for air.

“In three minutes,” he said, glancing toward the viewport, “I’ll be there always. In the light of the constant moon, I’ll be forever the wolf.”

Rowland’s nose bled. Her vision swam.

“Please…”

Fleming convulsed. When he straightened, his teeth had lengthened; his face pushed outward into a snout.

“Geostationary orbit in one minute,” the computer said.

It was the last thing Rowland heard before the dark took her.

“UEA Lunar Station, come in please,” the shuttle pilot called. “UEA Lunar Station, this is UEA Shuttle one-five-two, come in.”

The mission commander entered the cockpit.

“Anything yet, Major?”

“They decompressed the wheel, Sir,” the pilot said, “but nobody will answer my calls. It’s just been… weird noises coming back.”

“Weird noises?” the commander asked. “What kind of weird noises?”

The men looked out the shuttle’s cockpit window at the station, alone and backlit by the lunar surface.

“I’m embarrassed to say it, sir,” the pilot said.

“Out with it, Collins!” the commander barked.

“It… it sounded like a howl, sir.”

Troy Larson is a writer, digital content creator, and broadcast veteran with hundreds of podcast and broadcast credits to his name. Reach out on Facebook and on Instagram.